________________________________________________________

Sylvia Eckermann

n o w h e r e – ein

welt raum spiel

I treat Wittgenstein's propositions

more like axioms. When I negate the axiom,

'We make ourselves a picture

of the world' and say, 'We make ourselves a world

from a picture' then

I create the whole of Constructivism.* Heinz

von Foerster

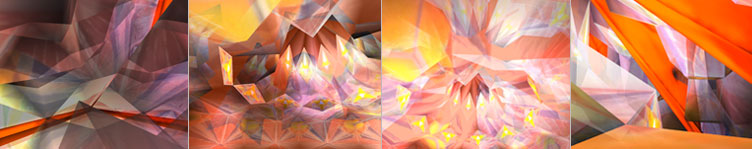

n o w h e r e is a gamemod, a modification

of the Egoshooter Unreal,

in which the player can move freely in any direction

in virtual, three-dimensional space.

Architecture, sounds, spoken text

and pictures support the immersive effect of this medium.

The choice of

free flight through space and time as a metaphor reflects the world of

thought

of the group of artists and architects that came together in the Gläserne Kette (The Crystal Chain)

correspondence [initiated

by Bruno Taut in December 1919] to share ideas.

Mere depiction was not the aim of our work, neither the transfer of the

two-dimensionality

of the sketches, designs and drawings into the third

dimension, but rather the enticement of

the viewer into a "dream

world" of utopian ideas and their simulation. Thus, in n o w h e r

e

Wenzel Hablik's outer-space painting Sternenhimmel [1909] appears

as a dense, sometimes

concave, sometimes convex cosmos of worlds moving

in an unknown system with satellites,

suns, conglomerations of stars,

flying machines and airborne colonies.

Some of these celestial

bodies are

taken from text fragments from Paul Scheerbart's Glasarchitektur, a work by the

man of letters who died in 1915 and who

very much influenced the proponents of

the Gläserne Kette: "Paradise

beetles, lightfish, orchids, shells, pearls, diamonds and so on—

all

of this together is the most magnificent on the surface of the earth—and

this is all to be found

in glass architecture. It is the highest — a

pinnacle of culture." (in: Glass

Architecture, 1914)

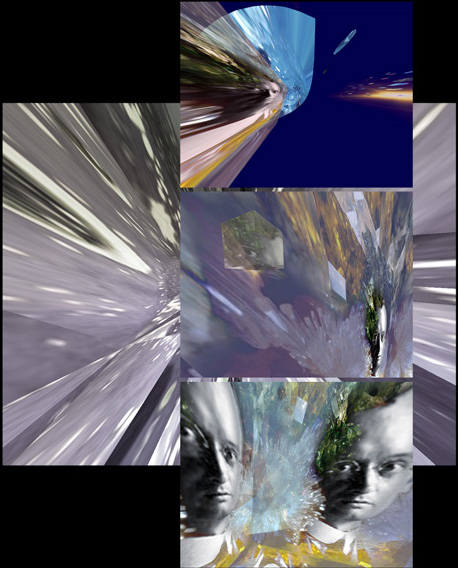

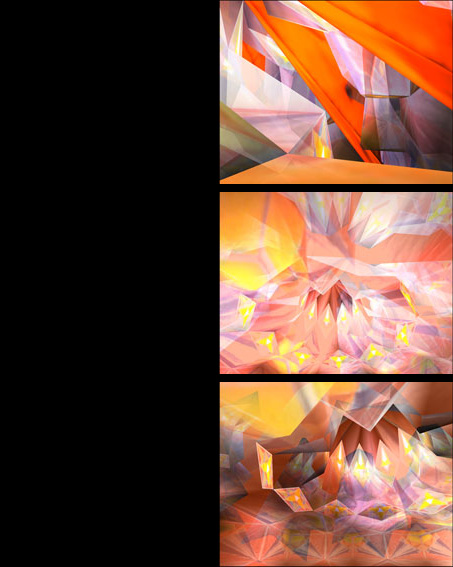

A planet cluster beams the visitors, as navigating cosmonauts, into the

contemporary

architecture

shining in many colors quoted by us. "Happiness

without glass—how dumb is that!",

"What would construction

be without reinforced concrete? "These sentences formulated by

Paul

Scheerbart penetrate the consciously fragmented architectural extracts

that appear

like dazzling spots and fade away again.

As in all parts of the work n o w h e r e one will also be able to discover

a crystal here,

in whose faceting the cosmos is reflected in its entirety.

This crystal functions as a transition

like a wormhole—as a link

up to the starting point. Crystal, an important form to which not only

our protagonists related, penetrated by light, unifying outside and inside,

simultaneously

form and spirit, an inorganic material growing similarly

to a biological organism, is penetrable

in n o w h e r e — a relationship

of reciprocal transmissions and penetrations of form just as of meaning.

And—as if one were inside a multi-faceted macrocosmos — the polygons

that delineate the inside

become an immersive kaleidoscope.

A particular crystalline form is assigned to Wenzel Hablik, Bruno Taut,

Wassili Luckhardt,

Hermann Finsterlin,

Hans Scharoun and other proponents.

Like a chain, link after link lines

up on invisible threads. They seem

to be enclosed in this form that appeared so important to them —

like

the insect caught up in resin that

has become stone. Where they twinkle

like inclusions in the light

of the stars there are other links and invisible

portals.

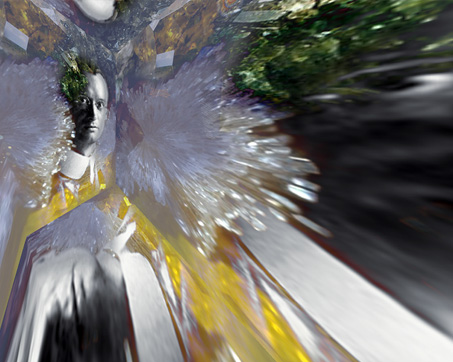

One enters a prismatic lucent cylinder in which mountain panoramas

revolve through fog.

This place

is dedicated to Alpine Architektur [1917-1918] by Bruno Taut, the spokesman of the

Crystal Chain

group

of artists and architects. His drafts become real in the mountain

chains— crystal cavities adorn the

crevasses, chrysocolla, amethyst

and bismuth tower upwards like

futuristic buildings competing with

the mountain tops. Here too, the previously mentioned crystal again

leads back to the cosmos.

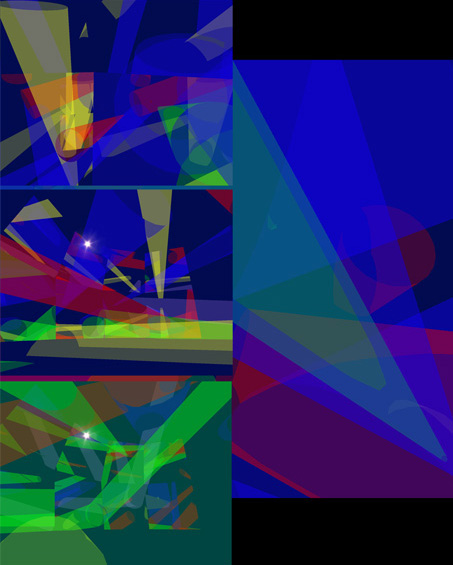

The area dedicated to Wassili Luckhardt does not tell of the vastness

of the starry sky

but of the stronghold of fortress construction.

His designs for buildings of worship [around 1920]

are external views

of crystalline-formed glass architecture that are interpreted as a

possible

interior view in the virtual architecture n o w h e r e.

The sparkle around Wenzel Hablik's crystal is the transition to his Schöpferische Kräfte [Creative Powers]

— a series

of etchings [1912] that tell of the becoming and being of crystal,

of birth, becoming and death.

The cosmonaut — the visitor — in

n o w h e r e will be able to discover this and much more as he flies

on his

freely chosen path through the cosmos of the Gläserne

Kette.

Come and see Utopia and start out from n o w h e r e !

|